Righting Pike’s Wrong

Preparation is everything.

Standing at the edge of one of my previous jobs, I could easily see the Front Range of the Rockies stabbing their defiant fists into the air. The most prominent fist is Pikes Peak, what the brochures call “America’s Mountain.”

One cold morning, while sucking down copious amounts of coffee and staring off into the vastness of the desert, I was reminded of Zebulon Pike and how mistakes often turn into something else entirely, how mistakes can actually be a good thing.

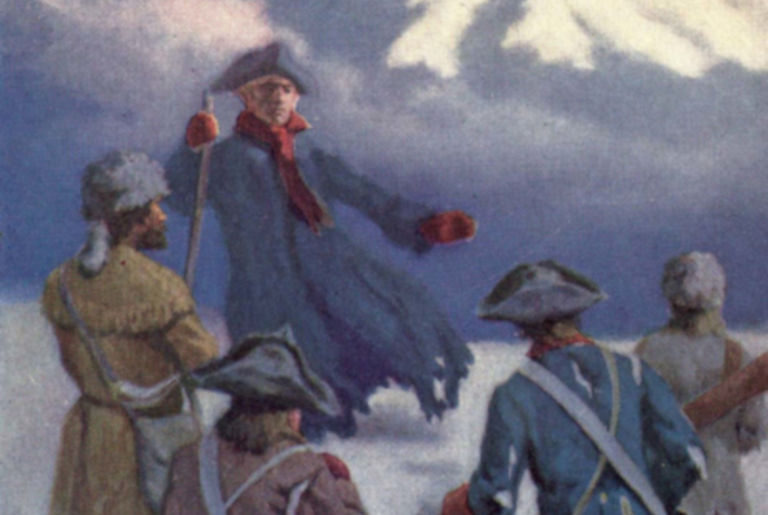

For the history buffs out there, Capt. Zebulon Pike first spotted what he called “the Grand Peak” on November 15, 1806. As he pushed up the Arkansas River into what is now Pueblo, he decided to attempt a climb of the mountain that now bears his name. On November 24th, a four-man climbing party left their camp to begin their ascent.

Due to Pike’s distance miscalculations, it took two days, not one, to reach the base of the mountains. On the morning of the 26th, the climb began. However, continuing miscalculations of distance and deteriorating weather prevented them from reaching the summit by nightfall.

The following morning, Pike arrived at the summit. His climbing party was treated to a spectacular view of oceans of clouds below them and a panoramic blue sky above. Their view also showed that due to their previously obscured view of the peaks from the valley floor, they had climbed the wrong peak and were standing atop 11,499 ft. Mt. Rosa.

The Grand Peak was fifteen miles away.

Pike wrote in his journal:

…here we found the snow middle deep; no sign of beast or bird inhabiting this region. The thermometer which stood at 9° above 0 at the foot of the mountain, here fell to 4° below 0. The summit of the Grand Peak, which was entirely bare of vegetation and covered with snow, now appeared at the distance of 15 or 16 miles from us, and as high again as what we had ascended, and would have taken a whole day’s march to have arrived at its base, when I believed no human being could have ascended to its pinical [sic]. This with the condition of my soldiers who had only light overalls on, and no stockings, and every way ill provided to endure the inclemency of the region; the bad prospect of killing any thing to subsist on, with the further detention of two or three days, which it must occasion, determined us to return.

Zebulon Pike never made it to the top of his own mountain.

I find all this interesting from a leadership development point of view. After all, leaders are not perfect; they make mistakes.

To prevent mistakes or to correct them before they become disastrous to the organization, thousands of books have been written on the subject. There are books on introspection, books on how to be the perfect leader, books on how to be the perfect leader while introspection puts you on your head.

Leaders are prone to mistakes, even the best of the best.

While some leaders reach the peak, others do not. What is the difference when we all make mistakes?

Preparation.

Recall that Pike’s climbing party “had only light overalls on, and no stockings, and every way ill provided to endure the inclemency of the region.” In short, they weren’t prepared to make the climb. They didn’t have the appropriate clothing to endure the rough conditions of that November in Colorado. Had Pike believed there to be more than desert in the West, he would have prepared his troops better, let them take their coats and hats and gloves and scarves.

Had he been prepared, Pike might have reached the summit.

Using Pike’s story as allegory, how do leaders prepare for their climb up a mountain, from the mail room to the corner office, from start to finish? That mountain of a career is wrought with peril, is it not?

There are cold spots, crevasses, ice caves, even abominable snowmen. There are mistakes to be made along the way to the top, and any leader who tells you he or she has never made a mistake—has never been totally prepared for the climb—is a liar.

When I talk about preparation in leadership, I am not asking if you have a business card like Patrick Bateman or a new laptop with all the distracting bells and whistles. I am not asking if you have your leather-bound journal or your Montblanc fountain pen, even if you have an idea to move the organization forward. We all have ideas, even those who do not lead. Ideas are thoughts, born through the interaction of synapses and every one of us has an idea (or two).

Preparation is about having a plan of attack, being able to visualize the possible barriers to success and then being ready to conquer them with the proper tools.

Preparation is about surrounding yourself with employees who will climb the mountain with you, knowing the strengths and the weaknesses of those employees, and making it possible for them to reach the top.

Preparation is about paths (the trail you plan to use), about goals (the reason you’re climbing in the first place) and about strategy (knowing the tools to use and when to use them).

All leaders need to have a goal. You see a mountain in the distance and you say you’ll reach the top.

Many people don’t make it. They start out with shorts and slippers and expect to be warm at the top. Although they really wanted to climb the mountain, they didn’t prepare for the journey.

They didn’t learn from Pike’s mistakes and didn’t right his wrong.

If your organization needs Leadership Development, contact Wretlind Consulting Services, LLC to see what options are available for you.

goal setting leadership mistakes preparation resilience strategy